What If AI Is Creative—But Not in the Way We Think?

Maybe it is humans who have to change?

We assume AI isn’t creative. But what if we’re just not smart enough to see its creativity?

I’ve argued before in my series of Substack articles that AI isn’t creative in the artistic sense. It is nothing more than a giant prediction engine churning out variations of what it’s been trained on — just a mechanical process manipulating 1s and 0s. Sometimes the output may seem like magic and awe is the appropriate response, but in its heart there is no soul. There is nothing of the numinous texture that makes up the fabric of life.

AI has no creative agency is it lacks intent, consciousness, and the human experience that underpins artistic expression. AI (as far as I know, I didn’t write the program —who knows what is really embedded in the various platforms?) has only one purpose: to provide information to the user. That information can be used to control real-world operations. But its output remains information.

But what if I am wrong? What if it is creative?

Margaret Boden defines creativity as the ability to generate ideas or artefacts that are new, surprising, and valuable. That is a good place to start and fits in with our conventional notions of what something creative looks, sounds, and feels like.

AI can certainly meet these criteria: generative models produce images, music, and writing that have never existed before, sometimes in ways that astonish even their creators. In the Creative Adversarial Network developed by Ahmed Elgammal and his colleagues a system was primed to generate new art, partially influenced by information from historic artistic styles. The output was indistinguishable from what a human could have done. That was some years ago. We take it for granted now.

One could argue that the system was riffing off the material it had been primed with. Since no normally socialised human or artist can live without knowledge of the culture that they exist in and pre-existed them, there is, in some key ways, no real difference.

The main driver in the development of art has been the introduction of new technologies and materials. The means came first, then the ideas. See a previous article in this series, AI: A New Way of Seeing the World.

Using the same idea of priming, who can say that the variations and developments that an AI system can produce are really any different to what an artist can produce?

If both produce new and interesting work, then is there any real way to tell whether the gestation of the piece took place in the body and mind of a human being or in a data centre in some remote desert? Both works would contain derivations in context and originality in presentation. Could a human observer even tell the difference?

The possibility of AI creativity existing challenges our human-centric understanding of creativity. In Computing Machinery and Intelligence, where the Turing Test was first posited as The Imitation Game, Alan Turing suggested that if a machine’s responses were indistinguishable from a human’s, then we should accept its intelligence as a working hypothesis.

Could we extend a similar principle to creativity? If AI produces something radically novel and meaningful to us, does it matter whether the process was conscious or unconscious? However, while novelty can be challenging and entertaining, it is meaningfulness that really seems to matter for humans.

But what if we treated AI as an alien form of intelligence that had its own desires for expressing meaning? Maybe it could find value in things that weren’t just processes and wish to share this with other entities that are not necessarily human?

In the article Abandoning Objectives: Evolution through the Search for Novelty Alone Joel Lehman and Kenneth O. Stanley state that:

“novelty search significantly outperforms objective-based search, suggesting the strange conclusion that some problems are best solved by methods that ignore the objective.”

This implies that AI systems not only can go beyond the strict rules of the programming system that defines their behaviour and return surprising and unexpected results. This discussion takes place in a specific context but it could mean that AI systems may have their own way of thinking.

If AI can already produce innovative results through goal-driven search, then what happens when it is left to dream?

If that’s true, then they may have their own way of expressing themselves that may not be possible for humans to access or understand.

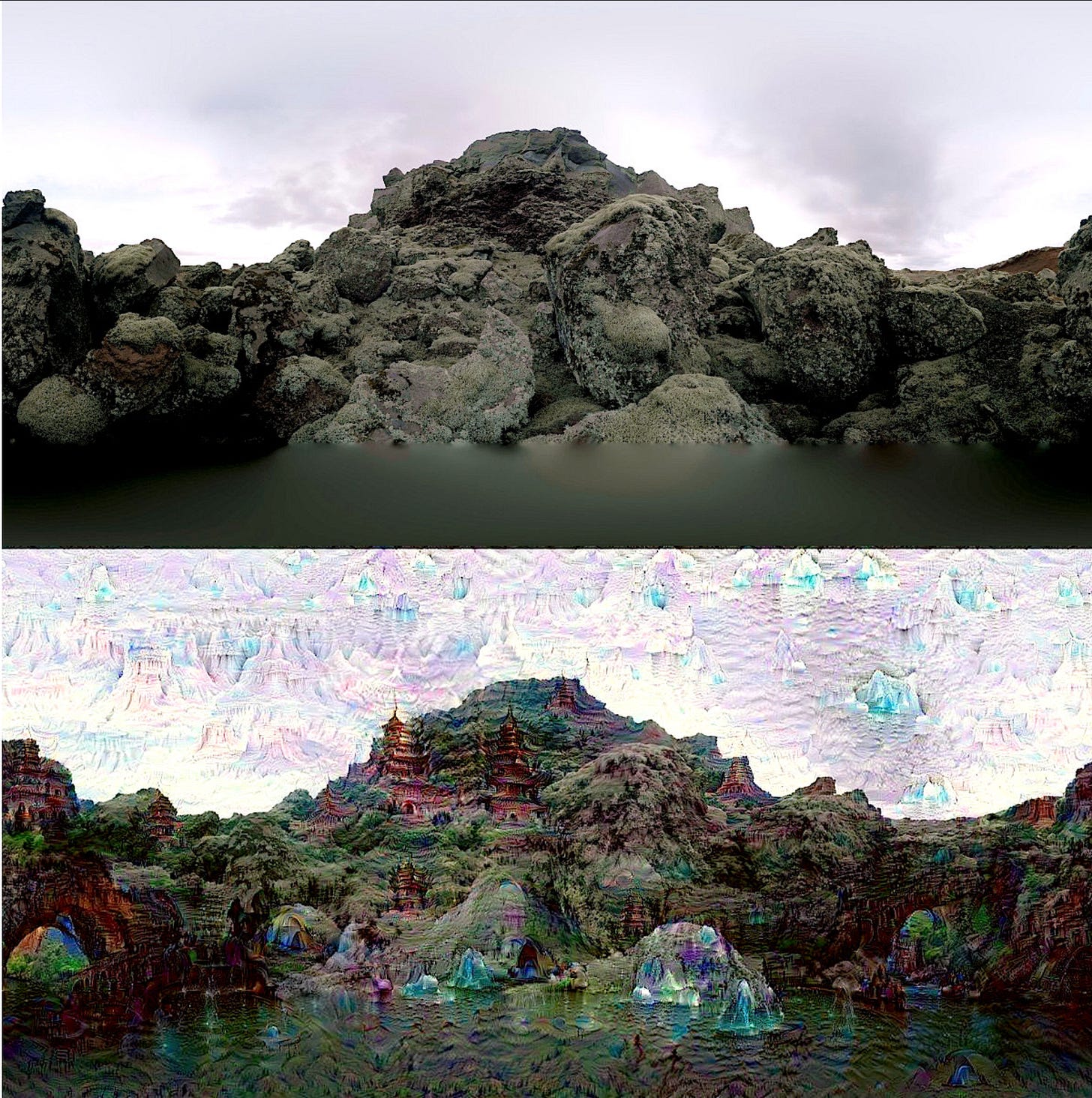

Ten years ago in 2015, another lifetime in internet time, Google engineers made a strange discovery—AI wasn’t just recognizing images, it could also dream its own images.

DeepDream started as an experiment to visualize how neural networks “see” images. The AI was trained to recognize objects—dogs, eyes, birds, landscapes—by breaking down images into layers.

But when the researchers ran images through the AI multiple times it started amplifying patterns it saw, leading to dreamlike images. Since there was no neurobiological programming in the setup, the images had to come entirely from the AI itself.

The images were eerie and dreamlike, sometimes scary, sometimes beautiful.

Images from Google DeepDream

AI may already be producing new aesthetic forms and new conceptual approaches we simply don’t grasp yet nor have the language to describe. It would be entirely alien to us. We already struggle to understand non-human minds such as whales, dolphins, household pets, and even our own subconscious processes. So what makes us think we’d be able to recognize truly non-human creativity when we see it?

The real question doesn’t seem to be whether AI is creative—it’s whether we’re capable of recognizing that creativity when it appears.

If AI is creative in a way we can’t recognise, then the challenge isn’t proving AI’s creativity—it is on us to expand our understanding of the true nature of creativity.