Environmental Issues Cannot Be Solved by Laws Alone

The Need for Personal and Local Responsibility

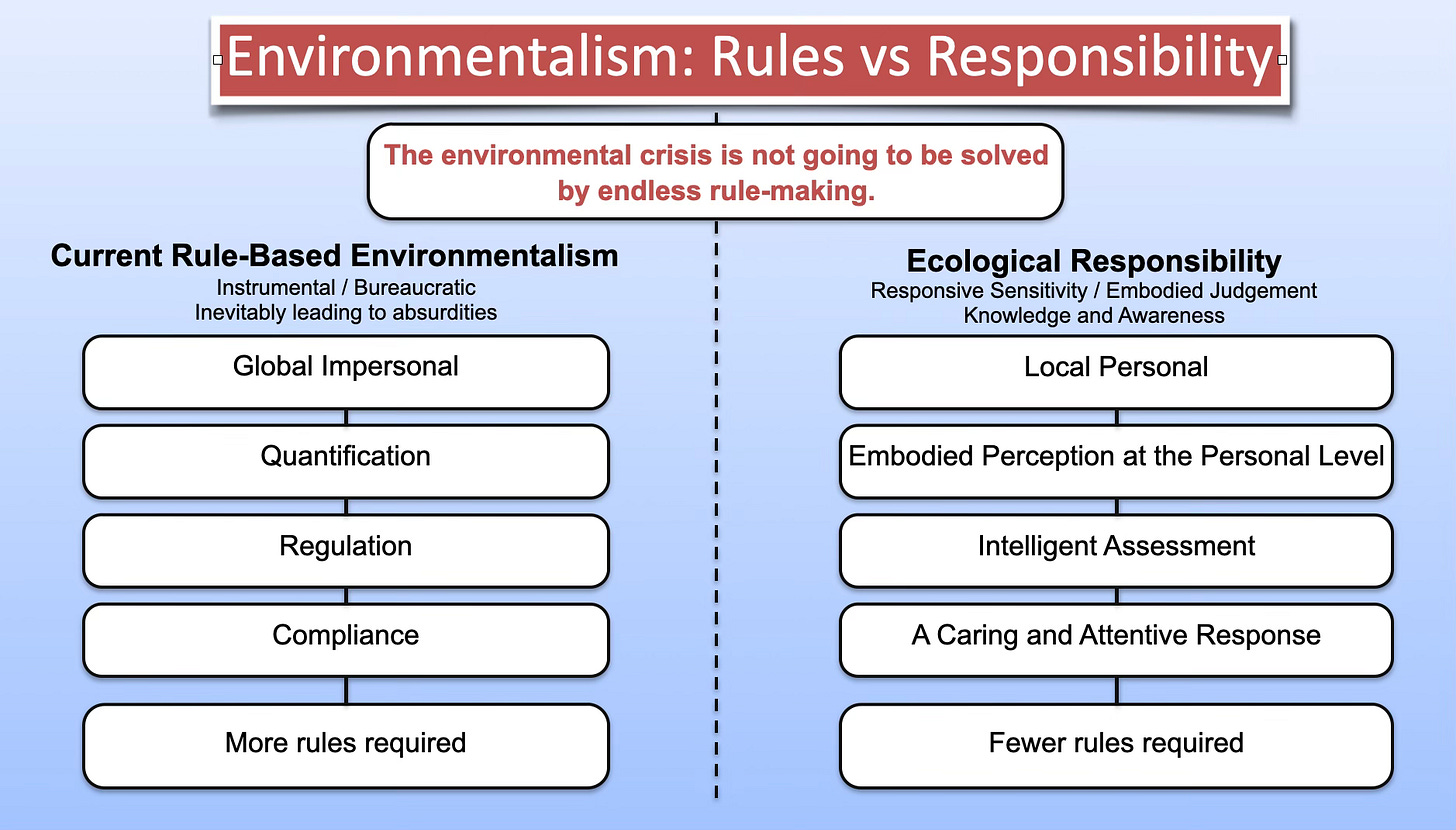

Modern environmentalism rests on an all-pervasive but rarely examined assumption: that a crisis caused by the application of rationality, reason and laws can be solved by further regulation, rationalised targets, and yet more compliance and restrictions. By framing the issue as a technical and administrative concern we are using the very same thinking that created the problem.

So clearly, we have to do some innovative thinking.

The philosophical roots of our present collective problem-solving, which include the superordinate emphasis on rules, duty and obedience, can be traced to Immanuel Kant. He formalised a model of moral reasoning that still structures European governance. Kant’s ethics grounded moral worth in duty rather than inclination, obedience rather than responsiveness, and universal law rather than contextual judgement. Moral action, for Kant, was valuable precisely insofar as it abstracted itself from circumstance, emotion, and personal experience.

“Thus the moral worth of an action does not lie in the effect expected from it, nor in any principle of action which requires to borrow its motive from this expected effect. For all these effects—agreeableness of one’s condition, and even the promotion of the happiness of others—could have been also brought about by other causes, so that for this there would have been no need of the will of a rational being; whereas it is in this alone that the supreme and unconditional good can be found. The pre-eminent good which we call moral can therefore consist in nothing else than the conception of law in itself.” Groundwork / Fundamental Principles.

This is a perfectly logical but quite insane conclusion. In his defence, one has to understand that Kant was attempting to create a logical structure to supersede the all-pervasive culture of superstition and personal caprice that existed before him. He did this by laying the groundwork for a conception of reasoned rule-making that displaced morality as a true guide to behaviour and action. This ended up being a conception of reasoned rule-making that claimed that the rule itself was inherently moral regardless of its consequences. While Kant’s intent may have differed, ethics came to be removed from how people really are and how they behave to beings conforming to, essentially made up, rules administered from above by the power of reason.

Rationalisation became the major determinant of human behaviour.

In much of Northern Europe environmentalism is now expressed almost entirely through Kantian forms: regulation, duty and compliance. Moral seriousness is granted by adherence to formal rules. Responsibility is a function of obedience.

All this rule-making and its consequent enforcement has the appearance of being ethical and feels rational because it is internally coherent. But because the logic makes sense in itself it doesn’t necessarily make sense in the world.

The ecological crisis did not come about because there was a lack of rules. It came from a Kantian worldview that objectified the world as a system to be managed, and a resource to be optimised. The products of the industrial monoculture, its associated technocratic planning, and highly extractive economic systems were not failures of rationality; they were expressions of it.

Environmental policy attempts to remedy the consequences of material exploitation on a grand scale but the mode of thought that created the problem in the first place remains the same.

So now we have an ironic state of affairs. A crisis that is a result of the supremacy of abstract reason is trying to be resolved by more of the same kind of thinking.

But laws, no matter how worthily framed, do not teach attentiveness. They do not foster or cultivate care. They are not capable on their own of creating the kind of relationship that we need to have with the world. They can only control behaviour within an abstract framework created by persons and institutions mostly unknown.

It feels as though the only available lever to effect real change is further regulation. All that means is that we will regulate ourselves to death. Life itself will become reduced to a Kafka-esque absurdity.

A very different way to think about our crisis is to not rely on someone, somewhere making some beneficial all-encompassing rule. The default question when confronting an issue would not be “What is the rule?” but “What does this place require now?”

The issue with legislation is its isolation of responsibility. As long as you obey a rule then you are a good person. The problem with abstractions defining your morality is that you are alleviated of the responsibility for doing what you know is right. It is not about what you are allowed or not allowed to do. It is about asking, what are the real-world consequences of my actions? And what can I do to effect real and important change regardless of what some remote lawmaker says?

This is not an argument against reason, nor an appeal to the bad old days of superstition. It is an argument against mistaking abstract notions of order for moral depth.

Our environmental reality is irreducibly local, time-bound, and relational. It has nothing to do with arbitrary and wishful targets.

The discomfort this idea creates is understandable. Northern European cultures in particular are deeply invested in order, duty and obedience. Formal systems see personal human judgement as unreliable and risky.

But environmental catastrophe does not care about the man-made rules that created it in the first place. More rules, more disastrous outcomes. This is not anarchy, this is personal responsibility. It is not about regimentation but individual responsibility and the only duty should be a duty of care to ourselves, our community, and the world in which we live. Not duty to some fabricated set of instructions to control behaviour.

Unchecked, present day environmentalism will continue to generate more rules, more enforcement, and very likely more resentment without being able to change or prevent the destruction of the world around us.